In a recent group discussion, nickel boy Filmmakers LaMel Rose and Jocelyn Barnes take a deep dive into their ambitious adaptation nickel boy. The duo turned Colson Whitehead’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel into a bold first-person narrative film that not only stuck to the script but redefined what it means to watch a story.

Here’s how they do it, and what you can learn in your own work.

The beginning of cooperation

Roth and Barnes began their working relationship on Roth’s groundbreaking documentary Hall County This Morning Tonight. Known for its poetic visuals and intimate storytelling, the film commanded attention nickel boy Produced by Plan B and Anonymous Content.

Recognizing the need for a new, nontraditional look at the tragic story of reform schools, Plan B reached out to Ross. Not only did he insist on directing, he also insisted on co-writing the script with Barnes.

“I thought Jocelyn needed to write with me,” Ross recalled, emphasizing the trust and shared vision that guided their work.

Read more: 3 Tips Screenwriters Can Learn from Directing

Adaptation of Pulitzer Prize-winning novel

adapt nickel boy— a story rooted in the harsh realities of the Dozier School — was a daunting but inspiring process. In their adaptation, Roth and Barnes respected the novel’s emotional core while reimagining the film’s storytelling.

They highlighted a key creative choice: using first person perspective Let the audience immerse themselves in the life experience of the protagonist Elwood. This stylistic decision turns the camera into “the character’s organ,” as Roth describes it, rethinking trauma and memory in ways that traditional cinema rarely explores.

“Movies often take inspiration from theatre,” Ross explains. “You are the ghost floating in the story. But when the camera changes to the character’s eyes, you start asking: Where are they looking during trauma? Where are they going? us look?

Nickel Boys (2024)

writing nickel boy through images

Ross and Barnes discuss their visually driven writing process, which prioritizes cinematic language over traditional dialogue. Their goal is to create “adjacent images” – moments of sensation and experience rather than explicit narratives. Scenes are written to be “aware,” encouraging the audience to physically feel the story rather than just observe it intellectually.

For example, Ross points out a powerful moment where dialogue was completely removed. “We had Ethan speaking the lines in his head. It puts the meaning in the audience’s mind. That’s what makes a movie,” he said.

Barnes adds that this approach required rethinking traditional screenwriting rules: “We didn’t want to be tied just to the plot. The emotional transference of love between characters became our organizing principle.

Read more: How visual effects allowed Keanu Reeves to speak only 380 words in John Wick: Chapter 4

The role of time and memory nickel boy

Time, both as subject and as tool, plays a central role in their adaptation. “Much of the film reflects on the process of remembering,” explains Barnes. “It’s not just about moving forward, but about deepening—inviting the viewer to actively reflect rather than passively consume.

This deliberate pacing allows the film to respect the weight of history and trauma without relying on overt depictions of violence. Ross emphasized that the film’s purpose was to focus on vision and the beauty of life, not just its cruelty.

“If all you get from this movie is trauma, then you’ve been so visually traumatized that you’ve missed the experience,” he argued.

Nickel Boys (2024)

The new language of cinema

For Ross and Barnes, nickel boy This is not just an adaptation but an experiment in cinematic grammar. The film’s visuals challenge viewers to engage with the storytelling in different ways. By blending documentary techniques, poetic visuals, and meticulous research—including Dozier Reports and oral histories—the filmmakers created what Ross calls “monuments of experience.”

“Images speak to images. They don’t speak to the real world,” Roth noted, emphasizing the potential of film to transcend simple reality and provoke deeper reflection.

larger conversation nickel boy

The discussion ended on a thought-provoking note, with the panel discussing the challenges of telling stories about systemic violence. How does an artist transcend familiar narratives?

Ross encourages filmmakers to embrace complexity, draw inspiration from contemporary photography and reject the reductive tropes of mainstream cinema.

“If all our stories were about conflict, that’s what we see in the world,” added Barnes. “We need to challenge ourselves to create stories that deepen, expand and ultimately reflect more.”

Nickel Boys (2024)

Turn bold visions into reality through screenwriting

Ross and Barnes nickel boy A testament to the power of visual storytelling and collaborative art. Their work challenges traditional screenwriting norms while respecting the novel’s themes of resilience, love, and memory.

For filmmakers and writers, their approach is a masterclass in how to reimagine a powerful story for the screen—one that lingers long after the credits roll.

Read More: Unconventional Story Structures for Screenwriters

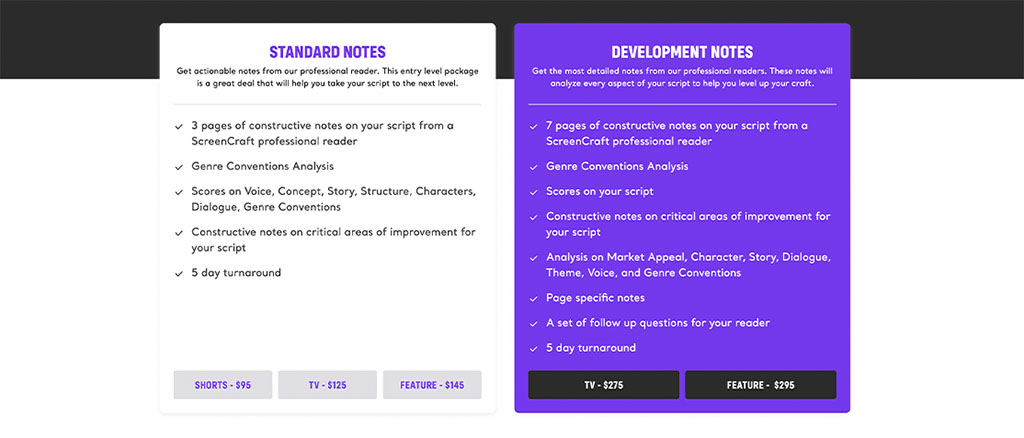

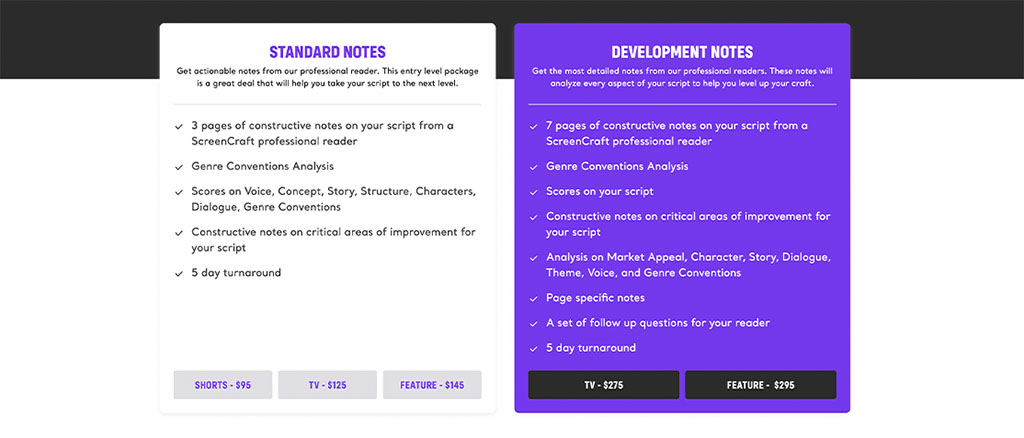

Get actionable drama notes from professional readers with real industry experience!