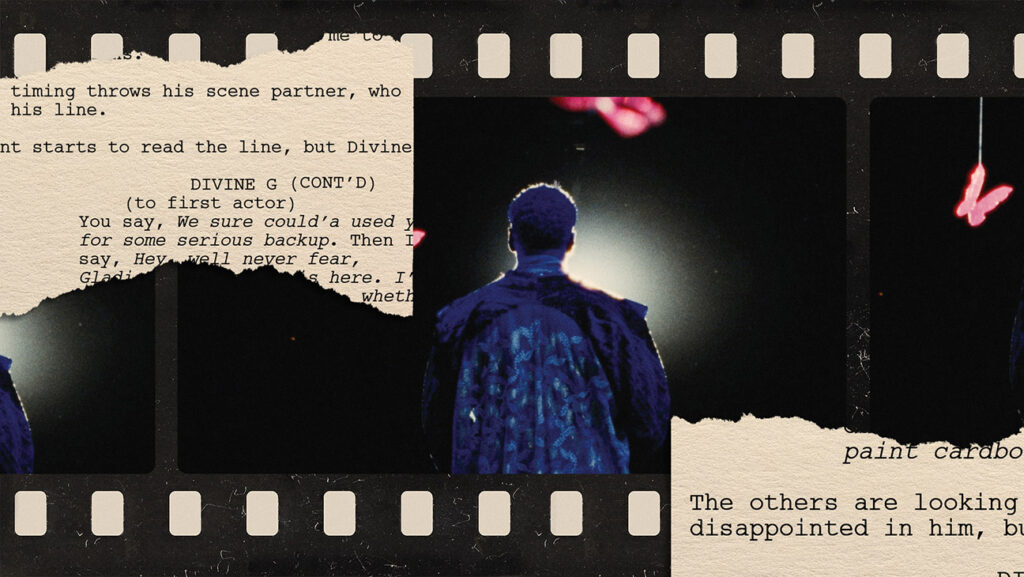

Make script Sing — the story about a real-life theater company called Arts Rehabilitation at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in upstate New York — proved to be an extremely difficult one for screenwriters Greg Cuedal and Clint Bentley. Subtle stitching. “We hold this program and what they’re doing as sacred,” Bentley explained, adding that the stakes are high. “If we hadn’t done this movie well, it could have been in real danger. [currently incarcerated people’s] The ability to function in prison. In this scene, rehearsals are taking place for RTA’s upcoming drama, in which the film’s protagonist, based on the real-life character John “The Divine G” Whitfield (Colman Domingo), learns that he broke down on stage after his parole appeal was rejected.

Provided by A24

Kwedar and Bentley first learned about Sing Sing’s RTA program through an article in Sing Sing Esquirewhich prompted them to volunteer at the facility. Their story centers on imprisoned actors Divine G and Divine Eye, and the filmmakers’ invitation to co-write it made the script feel “alive in a way it never had before,” Cuedal said.

Provided by A24

dramatic dialogue in movies, Cracking the mummy coderemains unchanged from the actual script written by Brent Buell (the RTA volunteer played by Paul Raci in the film). “The juxtaposition of the playfulness of the work and its context creates a magical effect,” explains Kwedar. “Earlier, we met Burr, who invited us to New York for breakfast with some alumni of the program. Real Eyes of the Divine (actor Clarence McLean, who plays himself in the film) and Real Divine G (John Whitfield) was right there. “If we could capture the feel of this room, it could be special. “”

Provided by A24

The scene is after a parole hearing, where the evidence exonerating him has been thrown away and he learns that he will remain incarcerated. While his anguish over the news didn’t quite play out that way in real life, “the scene was grounded in a real emotional state,” Cuedal said. Bentley added that the process included discussing different scenes with Whitfield and MacLean, “making sure it was what the script needed emotionally at this moment. What would that look like? And never wanting to go to a place where they felt Something unreal, even if it looks a little different than what happens in real life.

Provided by A24

Domingo’s dialogue in the final cut of the film doesn’t sound exactly like what’s written on the page. He added – “You told us to trust the damn process, right? Well, the process is fucked” – in his anguish. Bentley said: “I don’t think we could have written that sentence – ‘This process is over’ – because it felt like it was too far a step. But that’s what the scene was about. Coming out of Coleman, it clarified that One scene. He was such a storyteller for us.

Provided by A24

Throughout the film, God G encourages God Eye to let down his emotional guard. “The character of the Sacred Eye, and what he represents, is someone with a plan to bring the threat of violence into this sacred space,” Bentley said. “To see our Holy G character go from someone who was really advocating for keeping any form of violence out of this space to someone who is now taking on this posture — showing a depth of desperation felt really important.”

Provided by A24

This line is a callback to the beginning of the film, when God G directs God Eye through a monologue. villageexplaining that while anger is the easiest emotion to play on, hurt is more complex and interesting. This line didn’t actually make it into the final cut. “We spent a lot of time making sure that this scene not only expressed the myriad of feelings that Divine G went through, but also harkened back to things earlier in the script,” Bentley explains.

Provided by A24

While much of the script underwent extreme evolution between drafts, some choice lines remained from the beginning. “I’ve worked with Clint for 14 years. He has a gift for being able to express something authentically from the depths of a character,” Kwedar enthuses. “Clint wrote some amazing moments in his first pass, like the button in that scene: ‘Are you done?’ “No I’m not, isn’t that funny?”

This story first appeared in the December Independence issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. To receive the magazine, click here to subscribe.