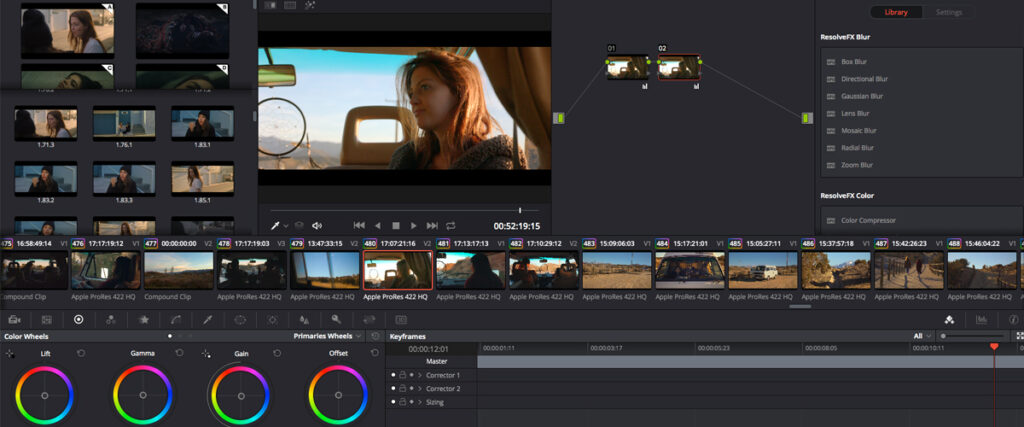

Over the years I have collaborated with other filmmakers on the color grading of countless films and encountered both creative and technical challenges along the way. Of all of these, by far the biggest hurdle to overcome was trying to recreate color contrast in a scene that had absolutely nothing to begin with.

This process almost always takes the same process in the color sessions I run –

First, the director or DP attends a look-shaping session, during which they share with me their creative ideas and most importantly their visual references. These references are usually screenshots taken from other movies of the same genre or tone, with the goal of replicating the same look and feel of the project at hand. But unfortunately, in many cases, it’s simply impossible to achieve what the filmmakers wanted without reshooting the footage…

Almost every time this happens, it has the same root cause: The film was shot without grade in mind and lacks color contrast.

Overall, shots are generally very warm, with few (or no) cool tones to be found. There are no practical lights with cooler color temperatures. There are no cool colors in the wardrobe. Just wash it with warm water and it’ll be fine…

I ran into the same problem many times with other color casts (blue, green, etc.) that seemed to dominate the look of the original footage. No matter what, the end result of our color sessions is always the same –

I had to inform the filmmakers why it was not possible or advisable to proceed with the grade the way they had previously suggested, and then we had to brainstorm ideas for alternative looks that would be feasible within the constraints of the original footage.

This situation can be easily avoided if I (or another colorist or production designer) are consulted during pre-production, as any potential problems can be nipped in the bud.

More specifically, the filmmaker asked me to create a vibrant, poppy, saturated look in post, similar to what you might see in the film spring breakers. While it’s usually relatively simple for myself (or any colorist) to achieve this type of look, the source footage doesn’t allow me to do so.

The stock is flat and lacks any pops of color in the wardrobe, production design, lighting and settings, leaving very little overall color information. On a technical level, the footage otherwise looks good and was shot on a RED/Alexa, but the shots don’t have enough color contrast to give us a choice of grades.

I could certainly try adding a bunch of contrast/saturation to the material and simulate color contrast in post by pushing the shadows and highlights in opposite directions, but that wouldn’t achieve the look they were going for. It’s too late…

By the way—— spring breakers What I’ve described is far from the only situation in which a lack of color contrast in a scene results in limited post-production options. In fact, almost no look or style (except black and white, bleach bypass, or sepia) can be fully achieved without considering color contrast from the beginning of the filmmaking process.

When I advise filmmakers on this issue, I always remind them of the following:

Removing color in post is easy, but adding color is difficult.

To give a very obvious example, imagine you photographed something in black and white. Would you take this footage to a colorist and expect them to turn it into color? Of course not. So why would you expect an image that contains very little color information to begin with to match an image that contains a lot of color information? it’s out of the question…

To clarify further, I’m not suggesting as a blanket statement that all films should be production designed or set in a way that allows for lots of pops of color. Every movie has different needs. My point is that if any colors are to be emphasized in post-production, they need to be present during production as well. Rather than a broad spectrum, you may only need to consider one or two key colors.

For example, there are many films that have a relatively limited color palette but use several complementary key colors at the same time. There may be a lot of orange and blue in the film’s costumes, set design, and props, and although the film may intentionally have a washed-out or desaturated look, the orange and blue theme can still stand out in class because it’s rooted in In the visual DNA of film.

So, when building a color palette for your film, how do you make sure you’re setting yourself up for success?

First, consider these 3 basic pillars –

1. Incorporate color into every step of the process

Let’s say you’re a project director. If a unique or specific color palette is important to you, you need to make sure it’s equally important to others on your team. This starts with pre-production, and by the time your footage reaches your colorist, most of the heavy lifting should already be done.

You need to talk to your DP and the people responsible for makeup, costumes, and sets/props and get your intentions clear early on.

If you have a specific color palette in mind, create a look book and share it with your team. Let them make choices based on yours that may not fit in with the lookbook, and decide when and where to make exceptions to the rules on a case-by-case basis.

As a director, your job is to make sure everyone on the team is making the same movie. Your direction must be cohesive, not just for the more obvious aspects of the project (story, characters, etc.) but for everything else. Includes color.

2. Use lighting to create color contrast

No matter how much planning you do in pre-production, there will always be certain scenes that require extra attention to color when shooting.

For example, you might shoot a night scene in a dimly lit house and ask the actors to wear white or pastel colors that don’t match your lookbook. Let’s say you can’t adjust the scenery or costumes for story purposes, but you still want to be able to create a vibrant look in the level, even though there are no vibrant costumes or props in this scene. What’s your job?

Focus on lighting.

There’s a lot you can do by using different color temperatures of different lights (not to mention using colored gels) to create as much color variation as possible in any given scene.

This is especially useful when trying to saturate a scene where the most vivid colors come from someone’s skin tone. Without warm utilitarian lights buzzing in the background, or cold light filtering through the walls in the background, the only saturated color is the actor’s skin tone. We all know how bad an oversaturated skin tone looks!

However, by using different color temperatures in your lighting settings, you can create a more vibrant look without oversaturating everything, and you can also control skin tones.

3. Be careful with IR pollution and ND filters

At least from my experience, the first two items on this list are really the foundation for achieving strong color contrast in a scene. That said, you still need to make sure the color palette you worked so hard to create is actually captured correctly by your camera. Unfortunately, some lens filters can seriously hamper your plans.

If you’ve ever shot with a cheap ND filter, you know how much color cast the tint of the filter glass can cause. In some cases this can be processed in post, but in other cases it’s simply impossible to make the color balance look perfect. Depending on the filter used, the colors in the scene, and the intent of the color correction, the color cast of a cheap ND filter may very well wash out/alter the colors you need to capture to achieve the look you want.

And more…

All cameras are susceptible to IR (infrared) pollution to some extent, but some cameras are more affected by movement than others. It all depends on the sensor and whether there is any kind of internal infrared cutting going on in the camera.

For those who don’t know, infrared light is a type of light that is invisible to the human eye but can show up on a digital sensor and cause certain colors to be rendered inaccurately in the final image. Infrared pollution is often exaggerated by using ND filters, which cut off most of the “good light” from reaching the sensor, but still allow unsightly infrared light to pass through.

This means a disproportionate amount of infrared light hits your sensor, which can make blacks look magenta and cause all sorts of other color shift issues that can’t be fixed in post.

Even if you buy an IRND filter (an ND filter that also removes IR), you still might not be clear. Your filter may cut too much or too little infrared light for your camera sensor, which is why cameras like the Ursa Mini Pro 4.6K come with their own IRND filter specifically calibrated to the camera. Unfortunately, no IRND filter works perfectly with any sensor.

So the point is not that you can’t use ND filters, of course you can! Just make sure you do plenty of testing with your chosen filter/camera settings to make sure the key colors you want to capture aren’t lost in the process. The last thing you want to do is spend weeks or months preparing for a shoot and then throw all that hard work out the window because you didn’t test a filter.

Assuming you do this (and the other steps in this checklist) correctly, you can rest easy knowing you have options to choose from later on. In the future, I will continue this article focusing on the post-production aspects of color contrast and we will look at how to enhance the color palette, so stay tuned!

If you haven’t already, be sure to check out my cinematic LUT pack here!

Please follow me for more similar content Instagram, Facebook, and twitter.