March 2, 1931 to July 16, 2024

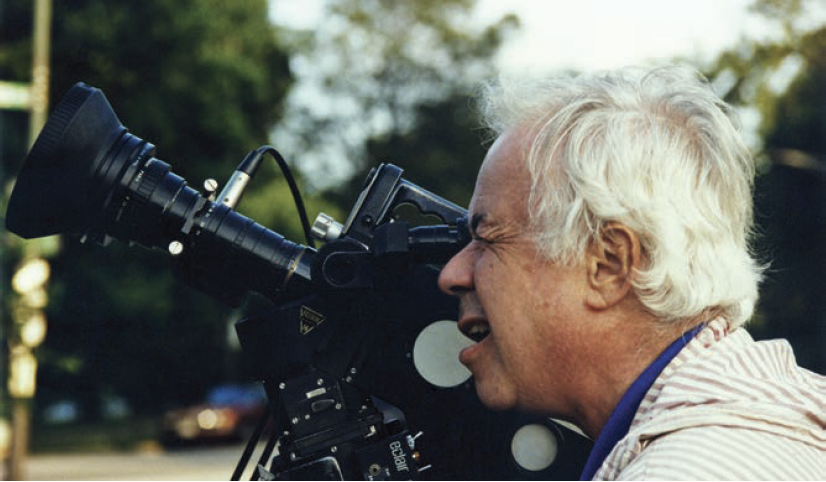

Manny Kirchheimer contains a lot: he is a film producer, an educator, a mentor, a friend, a husband, a father-and in his role, he is particularly proud of, being An editor.

“He just likes the editing process,” his son Gabe Kirchheimer said in an interview with Cinemontage. “I mean, he likes everything. But he really likes editing.”

As a hired editor, Kirchheimer died July 16 at the age of 93, amassing countless credits on television news and documentaries, but it was his adventurous spirit, unparalleled for his own uniqueness The non-extramarital editor, he is the most proud of and is very proud of it for it. He will be remembered.

“Manny’s film is unique and stylized,” said Stuart Stanley, retired sound editor and voice director. “His film editorial style conveys thematic visual canvas. The layering and rhythm of sound and music mixing needs explanation. Manny Kirchheimer’s movie is not a spoon feed piece. Show you a lot of various ingredients, among which the audience can choose and choose. ”

However, like all delicious dishes, Kirchheimer’s movies require a chef.

“Manny knew exactly how he wanted to bring together and achieve success in the film’s three-act structure,” said long-time assistant editor William Kruzykowski. “The Assistant Editor of “Elevated Station” released in 1981.

In that widely admired film, Kirchheimer trained his camera on expressive graffiti work that carved many New York subway trains in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

“It’s almost like Manny has already gathered the movie in his mind,” Cruzkowski said. “He just needs to shoot. Some of the locations he chose were riding from Manny on a bike ride List of places you noticed during your trip and then wrote them down with the intention of using them in future movies.”

With a preference for urban subjects and environment, Kirchheimer also produced a film about the Pier (the brief “Colossus on the River” in 1965) and crossed the suspension bridge (the short bridge in 1975 “High” ”). Other films examine the life of racial tensions (“Short Circuit” in 1973) and architect Louis Sullivan (“2006’s “High: American Skyscrapers and Louis Sullivan”).

Manfred Alexander Kirchheimer was born in 1931 to Jewish parents to Saarbrucken, Germany. Five years later, his father moved to Nazi-controlled Germany, alerting to anti-Semitism in Nazi-controlled Germany, and his family moved to the United States. After arriving in New York, the Kilchheimer people lived in Washington Heights.

Kirchheimer turned his attention to his personal history in the critically acclaimed 1986 film We Are So Beloved, interviewed Jews who escaped Germany like his parents and Start again in New York.

Kirchheimer introduced filmmaking at the City College of New York of New York of New York of New York City College and received his degree in 1952. One of his most important teachers is Dada Painter and avant-garde filmmaker Hans Richter. “Hans Richter had a big influence on my father,” Gabe Kirchheimer said.

“Hans Richter saw something different, and I think the excitement was my dad’s interest in movies. Then, after my dad graduated, they hired him to teach.”

So Kirchheimer embarked on a double track, pursuing his own independent nonfiction film project (mainly funded by his own resources), while making a living through teaching at NYPO and the School of Visual Arts. Kirchheimer is known to be a dedicated and engaging teacher who conveys his love and appreciation for film to his students in various forms.

“He is a legendary coach,” Gabe Kirchheimer said. “He has former students.”

Among them is Stuart Stanley, who recalls meeting Kirchheimer during the “one semester and only film major” at NYIT.

“My first day in class was an epiphany for me, and Manny became my mentor right away,” said Stanley. He studied filmmaking and recording under Kirchheimer’s leadership. and basics of editing.

“Manny asked me to take charge of the film equipment. I distributed the camera, the recorder, the lights, and then named it the student,” Stanley said. “He also allowed me to go to New York to get off work and learn how to fix the Moviola editing machine at Laumic Company, the largest editorial rental and repair facility in New York City at the time.”

Stanley found Kirchheimer encouraging when he made his first student film – even though Stanley himself had doubts about his project. “He said, ‘Your great movie is your personal project and you have to reach an agreement on that,” Stanley recalls.

“Manny is different from anyone I’ve ever met,” Stanley said. “He is so gentle, soft in speaking, keenly satisfying the needs of others without paying attention. He doesn’t push, push, manipulate, coerce or raise voice. He allows his students to be creative with freedom without intervention.”

Stanley was later recruited to work on the “elevated station” by Kirchheimer’s students, who were not alone, were forced to use fact-used filmmaking services.

“Although his films are basically not budgeted, it’s mostly his own money,” Gabe Kirchheimer said. He added that his father also received a gift from the National Foundation of the Arts and the National Humanities Foundation,” he added. payment. In 2016, he became the winner of the Guggenheim Scholarship.

Kruzykowski also found himself working at the “elevated station” and remembers first hearing about the film with the filmmaker at NYIT at lunch.

“He ended up asking if I was interested in helping him shoot,” Cruzkowski said. “For my memories, Manny never showed me a script or outline. He just talked about the fundamental meaning of making this new movie and Purpose. This intrigued me because he proposed the use of images, sound effects and the simplicity of music – without dubbing, narrative or synchronous dialogue – which would be the heart of his film.”

Kirchheimer served as editor of the network television project, especially in the 1960s and 1970s. “He works for all three letter networks and WNET,” Gabe Kirchheimer said.

“He works astronomical films, over a hundred networks.” Despite his success in this field, Kirchheimer sees these tasks as work. Sometimes, he finds himself working on a project related to social justice issues, such as inner city public schools.

But he likes to edit his own work the most—even if there is delay and uncertainty in truly independent filmmaking.

“There were some very difficult times and he didn’t have enough work,” Gabe Kirchheimer said. “I think that’s one of the reasons why these movies are going to be done, just to deal with the mix and all the labs.”

Kirchheimer accepted the arrival of digital editing, which allowed him to take the pace of his filmmaking in the decline of his career. His later films include “Spriphmasters” (2007), “Art Is Is…Permanent Revolution” (2012), and “Coffee with Jewish Friends” (2017).

“In the past, it took him a few years to finish a movie,” Gabe Kirchheimer said. “He then learned to use digital content and got the final cut 7 system in the house he used until the end.”

Kirchheimer’s wife Gloria and their sons Gabe and Daniel survived.

– Peter Tonguette