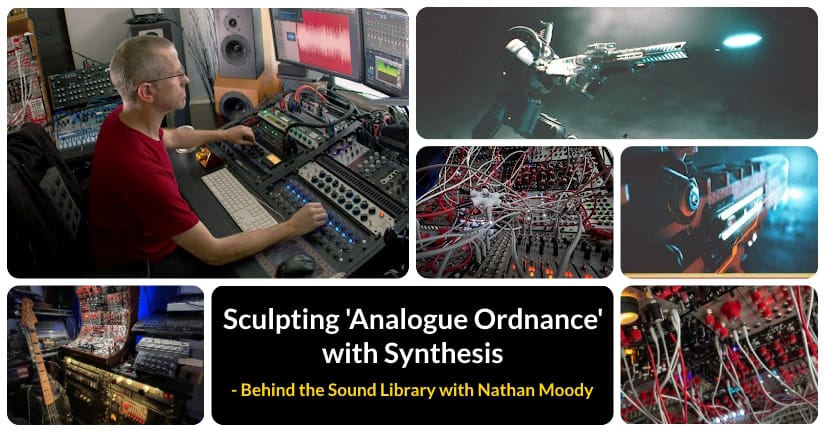

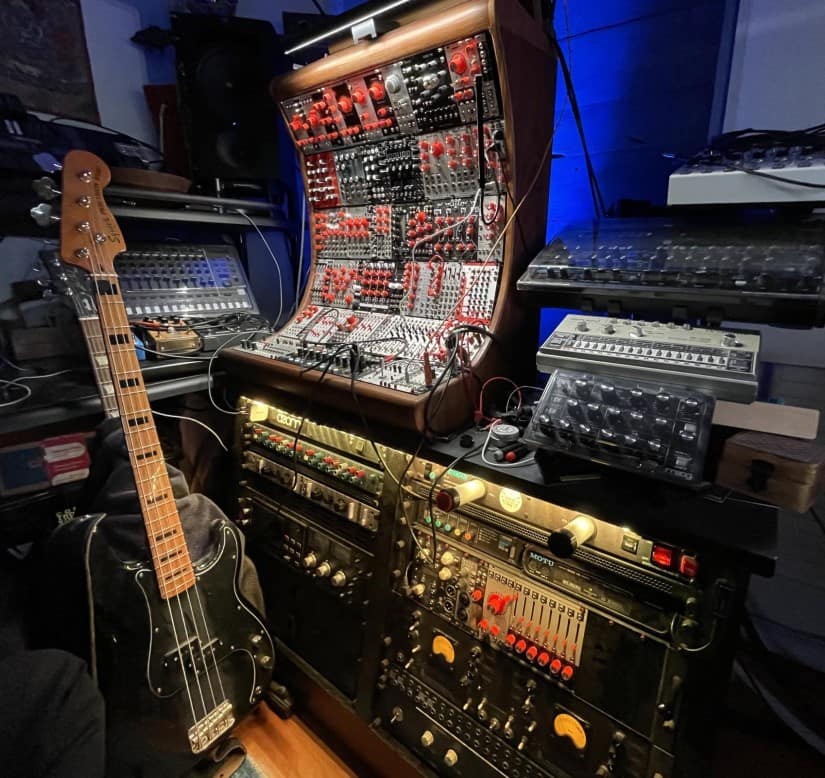

Interview by Nathan Moody, photos courtesy of Nathan Moody

timeHis library started like many before it: I was craving some material to satisfy my own needs, and after making it for myself… well, it all got a little out of hand.

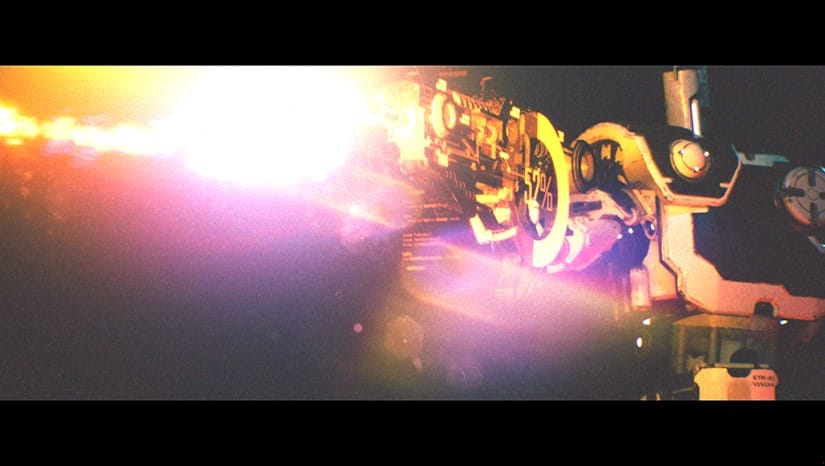

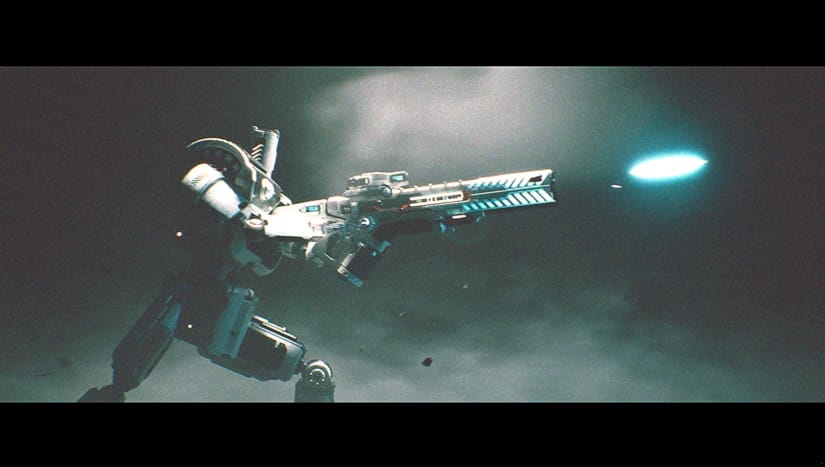

I wanted some new source layers for sci-fi weapon designs, and – since I mainly work with game audio – I wanted more variety in each sound file than I’d found in other libraries. I wanted layers, not a composite/completely engineered sound. Ironically, the indie game I’m working on never requires it… but it fills a need for my own library, so it’s still worth doing.

After a week of creating source material on my modular synth, I was amazed at how much material I made in such a short time, how much fun I had doing it, and how flexible it was to design and edit….. .without using any plugins during layer design process. As an experiment, I also started to master sounds from the analog realm. This small side effort turned into a months-long recording process, and analogy ordnance was born.

This article will discuss the tools, hassles, and triumphs of making this collection of sound effects come to life, as well as some specific tips and tricks for those using synthesizers for creative sound design.

Full hardware approach

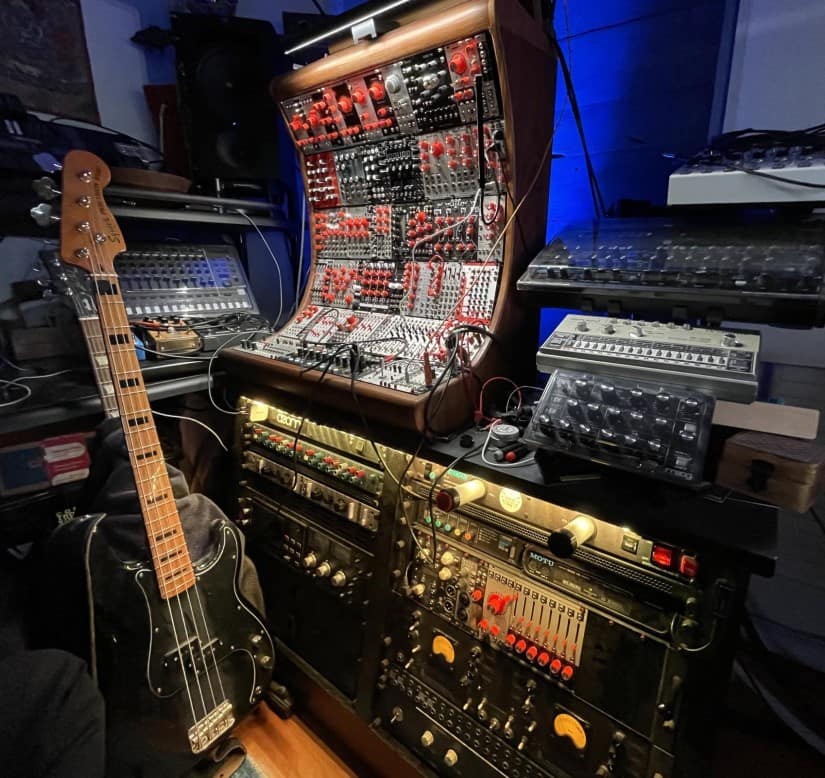

At first, I decided it was just a creative challenge to use only hardware synthesizers. Not having my usual software tools brought a different aesthetic to the materials and forced me to develop new habits. (Admission to my use of the word “analog” in a slightly “Dogme 95” style. While the audio signal path from the synthesizer to my audio interface is entirely analog, and throughout the mastering process, I couldn’t help but A few digital oscillator modules are used here and there, as well as a digital reverb/granular processor.

I find that tinkering with physical synths is faster than using soft ones.

Another benefit is that I find that tinkering with physical synths is faster than using soft ones. The reason is simple: I have two hands. I can design physical patches much faster than using a mouse in a virtual environment where I feel like I have one hand tied behind my back.

Results of labor: analogy ordnance

For this library I’m creating new custom and tinkering modes that I wouldn’t normally try with virtual synthesizers.

The final aspect of using physical hardware is embodied cognitionthe physical movement itself guides and influences a person’s thought process and how we make decisions. I first encountered this idea when I was a UX designer, and my first personal experience with it was how well I played Scrabble on my phone compared to playing with physical tiles on a board. How bad. For this library I’m creating new custom and tinkering modes that I wouldn’t normally try with virtual synthesizers. Different tools will lead to different results.

Another benefit is that, with a random voltage source and no separation of the control voltage and audio signal, modular synthesis can be a perfect variation randomization tool, as well as a huge surprise machine. More on how to tame these forces later in this article.

….if you accept that ephemerality…it’s a really fun way to quickly iterate on source sounds and single-layer creations.

One aspect of this approach to consider is transience. In order to design more sounds, you need to rip out the previous patches and start over. Unless you carefully detail your sounds and knob positions with notes and photos (which I definitely didn’t do), it’s nearly impossible to recreate complex synth sounds. My approach is to create a patch, extract every possible idea from it, destroy it, and move on. This is a challenge for a finished layered design – how do you iterate based on customer feedback? – but if you accept that ephemerality, and have the discipline to learn from each tinkering session, it’s a really fun approach for quick iterations of source sounds and individual layer creation.

Every synth patch goes through an analog compressor, Neve EQ and Overstayer M•A•S processor before it reaches the audio interface and my recorder, so these are my only “plug-ins” for the mix. The recording of these sounds was the first of two analog-to-digital conversions that each sound undergoes.

Full analog mastering

I worked as a professional mastering engineer for many years before switching to game design, and the hardware nature of sound design made me want to take this approach to the mastering stage as well. This is yet another creative limitation.

…the average analog mastering time per archive is less than two minutes.

I was concerned that this approach might take longer – printing each master has to be done on the fly – but analog mastering ended up averaging less than two minutes per file. This is two to four times the length of the file itself. I don’t believe digital methods are faster, which is a useful indicator for future project planning and time management.

The nonlinearities of real tubes and transformers always tickle my ears, as does the mid to high “lift” a pushing pentode can provide. Plus, really pushing the high-end, high-headroom analog-to-digital converters for some soft clipping adds a lot of aggression and bite. All of this feels like a good fit for the arsenal. I also use some mastering-grade saturators if I want more heat.

Passing the signal to an external device and back again is the second and final transformation the audio undergoes.

Passing the signal to an external device and back again is the second and final transformation the audio undergoes. Since I want to master my own material, the only thing that works is to give myself some time away from the material before making critical mastering decisions. The mastering process is done at the very end after all the recording is done, so that my short-term sensory memory can be reset and the work can be heard with a fresher perspective.

Tips and Tricks

A few key techniques help me stay inspired and productive while fiddling with knobs and managing a rat’s nest of jumpers. These techniques apply equally to virtual and hardware synthesizers.

• Trigger every sound on the grid. My system clock always runs at 120 bpm, and I prepare a number of clock dividers to accommodate sounds with longer amplitude envelopes. This makes triggering each sound (i.e. turning on its amplitude envelope) predictable, simple and automatic, especially when slaved to the recording DAW clock using a MIDI-to-CV converter. Press the record button, the clock starts counting, and the sound starts! Once the recording was complete, I removed the silence and separated each sound by one second.

• Small delays make big differences. I ended up ripping out all the tempo-synced delay mods for this project and replacing them with probably very short and fast delays. This helps make the creation of “polysyllabic” textures, Karplus-Strong synthesis, and smooth temporal modulation much easier.

• Audio rate modulation is your friend. Most sound designers know about frequency modulation and amplitude modulation, but it can be great to send audio to other timbre parameters. Audio rate modulation of filter cutoff, resonance, wavetable index, FM amount, and more can create stunning results.

• Envelope – Comply with everything. Amplitude envelope tracking is a powerful and expressive modulation technique. I found a phaser module that doesn’t have an internal LFO like most phasers; running two of them in series with the frequency driven by the signal amplitude is much better than just running a phaser with an internal LFO that can’t be overridden The patch provides more interesting results.

• Attenuation is critical. Most modulation signals are the full voltage from the source; for example, in Eurorack, the voltage might be 0-5 volts, or even 0-10 volts. This is too aggressive for most modulation needs. Sometimes even 0.05 volts is enough to bring some huge movement and change to the patch.

• Use sample and hold to implement changes. I have up to nine sample and hold circuits that are clocked to the same flip-flops, which themselves make the sound. This way, the iteration will be different each time the amplitude envelope is turned on. Mixing this technique with a completely out-of-sync modulation source is a great way to achieve truly organic results.

• Inexpensive digital effects chips may produce noise. When you’re tracking at higher sample rates than 48 kHz in the Eurorack modular format like I am, most digital effects modules (like delay and reverb) use cheap chips that won’t produce noise when you , hissing and noise where the internal clock whines. After making this discovery, I quickly removed all but one of the digital reverbs from the rack. Since most editors and game engines will want to apply their own reverb anyway, this does nothing to the individual source elements.

• Fix “bugs”, but not randomly. Use clock as audio input. Modulate something that probably shouldn’t be modulated, or something that reasonably shouldn’t be modulated with an audio rate signal. Don’t be afraid to try something that doesn’t work. Tear it off and start over. But be curious about a “wrong” technique, try it out, and see what doesn’t work so you don’t get stuck in the same trap or repeat a failed experiment.

• “Blind” patches. Set up a complete patch end-to-end, no need to listen on the fly. This is a good test of your compositing skills and habits, and can lead to exciting places you didn’t expect.

• Don’t fight the patch. If you’re having trouble fixing a patch, be bold: rip it off and start over. Don’t waste time trying to draw blood from the stone.

Nothing better, only different

Most sound designers have synthesizer virtual instruments, and many have modular synthesizers in their studios. What I wanted to do was use these tools to commit to a specific build kit framework, and – as another creative constraint – try to use no plug-ins at all during the design or mastering process. I don’t think this approach makes the library better or worse, it just makes it different because of the choices I had to make. But I think these choices bring an interesting aesthetic, and hopefully others will find something useful in their own sound design work.

Many thanks to Nathan Moody for giving us a behind-the-scenes look at making the sound analogy ordnance!